a review of

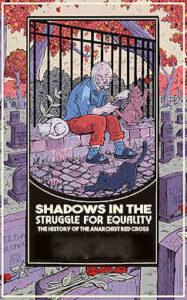

Shadows in the Struggle for Equality: The History of the Anarchist Red Cross by Boris Yelensky, Edited with a new Foreword and Introduction by Matthew Hart. Illustrated by N.O. Bonzo. PM Press, 2025

From Cop City to the Dakota pipelines and Jane’s Revenge to numerous struggles worldwide, anarchist organizers are relentlessly targeted by the state today as they have been for over a century.

Russian immigrant and revolutionary Boris Yelensky wrote this moving account of the Anarchist Red Cross (ARC) and related prisoner aid societies in Russia, the U.S. and Europe from the 19th century to the end of World War II. This book is a welcome affirmation for contemporary anarchist prison support groups, whose noble history is documented here.

It was first published by the Alexander Berkman Aid Fund in 1958.

Yelensky was born in Russia in 1889. He participated in the 1905 revolution there, afterwards fleeing to the U.S. where he co-organized the Philadelphia branch of the Anarchist Red Cross. When he and his wife Bessie moved to Chicago, they joined the Chicago branch of the ARC, a thriving organization with over 300 members.

Anarchists did not forget their own. Yelensky’s goal is to encourage others to “extend aid to the imprisoned, persecuted and impoverished comrades wherever they may be found.” The ARC saw prisoner aid as a form of mutual aid, working with imprisoned and exiled anarchists to help them survive state attacks. It was not just giving charity, but fostering their movement by supporting their most endangered comrades.

The new material in the 2025 edition is provided by Matthew Hart and N.O. Bonzo. Hart is a teacher and labor organizer from Los Angeles who helped re-establish the LA chapter of the Anarchist Black Cross in 1968. He has written a useful Foreword about Yelensky’s place and time, and provided an update of ARC activities, primarily in England, the U.S., Spain, and a few other countries. He has also provided four new appendixes and a fascinating and informative set of footnotes documenting and expanding Yelensky’s accounts.

The new edition is illustrated by N.O. Bonzo, a printmaker and illustrator who provides seventeen magnificent portraits, drawn with the artist’s characteristic William Morris-inspired appeal, of women and men from the prisoner aid movement.

These accounts are sometimes confusing because the organizations go through periodic name changes: some call themselves the Anarchist Black Cross.

Earlier groups were named the Joint Committee for the Defense of the Revolutionaries Imprisoned in Russia, and, after 1936, the Alexander Berkman Aid Fund. For ease of reading, I am calling the whole movement by the name used in the book’s title, the Anarchist Red Cross.

The overriding theme of this book is the sheer volume of need there is and has been for supporting anarchists imprisoned by, and families rendered impoverished by, various state regimes: Tsarist Russia; Bolshevik Russia; fascist Germany, Italy, and Spain; and various supposedly democratic regimes.

The most heart-breaking of these murderous regimes, to these activist communities, was the Bolsheviks. There had been so much enthusiasm when many anarchists, including Yelensky, returned to Russia in 1917 to work for the revolution. Their hopes were bitterly dashed.

In Yelensky’s words: “More than 90% of those who went back were later to die in the Bolshevik terror.” The Anarchist Red Cross was “quickly criminalized in the Soviet Union” where the new regime, themselves adept at underground tactics, ruthlessly targeted their former comrades.

The ARC assumed that, with the overthrow of the Tsar, there was no further need for prisoner aid in Russia. Yet they soon were back where they started. After leaving Russia in December of 1921, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and Alexander Schapiro “made an appeal to the world to aid those comrades who were suffering under the Bolshevik regime.” The movement ground back into action.

A second theme is the predictable, yet discouraging, conflicts among Left groups about the delivery of aid. There was an ongoing struggle with Social Democrats, who regularly excluded anarchists from receiving aid even if it was contributed by anarchist groups. In the end, only anarchists themselves could consistently be relied upon to get aid to anarchist prisoners. Even so, Berkman was a strong advocate for supporting all the radicals in prison, not just avowed anarchists.

In Appendix 4, Hart provides a sample of correspondence about this question between Berkman and Lillie Sarnoff of the New York Anarchist Red Cross. Berkman points out that imprisoned anarchists “share the things they receive” and insists that their aid work should not be based on approval of the particular political positions of the incarcerated radicals.

A third theme is the continuing importance of ARC publications. They never stopped trying to educate the public. The Joint Committee for the Defense of the Revolutionaries Imprisoned in Russia (Berkman, Goldman, and Rudolf Rocker) published the Bulletin of the Relief Fund of International Working Men’s Association for Anarchists and Anarcho-Syndicalists Imprisoned or Exiled in Russia. The London ARC published Hilf-Ruf (The Call to Aid)—an organ of the Anarchist Red Cross, written half in Yiddish and half in Russian. Many of the Jewish groups published material in Freie Arbeiter Stimme.

The movement generated at least three books (besides this one). Morris Beresin, who was imprisoned in Siberia after the 1905 revolution, escaped and came to the U.S., where he wrote From Chains to Freedom: Notes from a Fugitive Political Hard-Labor Convict. Berkman assembled Letters from Russian Prisons in 1925. Gregory Maximoff wrote The Guillotine at Work: Twenty Years of Terror in Russia, which started off as a pamphlet, but came in at 624 pages when it was published in 1940 by the Alexander Berkman Fund in Chicago.

Hart’s account shows that, when the Anarchist Red Cross returned in the 1970s and 1980s, their publishing commitments continued. The London ARC published The Black Flag, the Chicago group published the ABC Bulletin; the Melbourne group published Acracia and later Black and Blue. They were always teaching.

A fourth implicit theme is the nuts and bolts of the activists’ work. They were very hands on. They were not just writing checks. They were all volunteers so none of the funds went to administration. They raised money in the usual anarchist ways: benefit concerts; personal appeals to unions and fraternal organizations; films, outings, and lectures; sale of literature; and subscription lists.

Riffing on the common anarchist practice of themed dances, they invented the Arestantin [Prisoner’s] Ball, including costume contests and elaborate tableaux re-enacting scenes of oppression and resistance. People who themselves had little to spare contributed willingly and repeatedly to these activities.

They wrote personal letters to starving and frightened people, establishing bonds and providing a lifeline. They published prisoners’ letters. They sent specific items that prisoners needed: food, clothing, medicine. After learning that a lot of the imprisoned anarchists were learning new languages to pass the time, they sent dictionaries. People delivering the aid took great risks, especially in Bolshevik Russia. They often had to travel to distant prisons and camps and risk their own arrest to deliver much-needed packages.

Hart’s supplement tells the story of Albert Meltzer and Stuart Christie bringing back the movement in London in 1967. It revived soon thereafter in Europe and the U.S. The renewed London ARC was a cross-generational organizing site. Hart writes: “The group acted as a hub where generations of anarchists and revolutionaries came together to share ideas, theories, and strategies for changing society in a fundamental way. In many ways it helped the older generation pass the baton to the next generation.” This is a fascinating glimpse into the daily work of the movement, and I long for more.

Yelenksy is a skilled storyteller. Yet, I wish he had included more detail about women’s contribution to the prisoner aid projects. We know, for instance, that Bessie Yelensky was secretary of the Chicago ARC group, but nothing about what she thought or did. Hart notes that Bessie’s activism “was just as significant” as Boris’s, but we can’t actually tell. Since they were life partners, Boris must have known about Bessie’s work, but it is not included in his account. Hart focuses more on major confrontations with authorities and ensuing court battles, rather than activist process. I wish he had said more about what the groups did, not just what they were accused of.

Yelensky was determined that the indefatigable labor of anarchists in organizing mutual aid for prisoners would not be forgotten, nor would the great hopes they had for social transformation.

Looking back at the process of writing his book, Yelensky mused, “It has also been pleasant to recollect the enthusiastic activity that existed in so many cities during the old days of the Anarchist Red Cross. There was so much willingness during that period to sacrifice a part of one’s life in order to help those comrades who needed assistance in prisons and places of exile.” Yelensky was aware that others had revived the movement, and determined to help them make a go of it by sharing earlier activists’ experiences.

Hart rightly notes, “He devoted a lifetime to help build a better world and to form and sustain an international chain of assistance for the oppressed.”

Kathy E. Ferguson teaches political science and women’s studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She is currently writing a book on all the anarchist women who weren’t Emma Goldman.