“Liberty without socialism is privilege and injustice; socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality.”

— Michael Bakunin

When more than a million people- visibly break out of forty years of totalitarianism in a relatively spontaneous manner, their opinions, ideas, and fantasies inevitably vary wildly. However, the statements, interviews, and documents of the Chinese students’ and workers’ movements that have gradually become visible in the months after the June 1989 repression reveal distinct patterns and common attitudes among vast numbers of people. Even if this material doesn’t delineate an explicitly “revolutionary” program, the perspective that emerges still. provides a wonderful breath of fresh air in a country long stagnant with authoritarian ideas and practice. Through this we can see a Chinese democracy movement that contains a molten mixture of many different ideas, many half-baked but all of them subordinate to the exhilarating actions of people refusing to be submissive.

The Early Peaceful Demonstrations

The unofficial Chinese student movement gradually gained momentum in a mostly clandestine form after the suppression of protests in December, 1986. In the spring of 1989, many observers expected a confrontation between students and the government on 4 May, the 70th anniversary of the May 4th Movement which in 1919 had delivered a crucial blow to the old feudal regime.

On 15 April the last major “liberal” within the government, Hu Yaobang, unexpectedly died. While Hu could hardly be considered a radical, he had achieved some favour among the people (but was dumped by the government) for defending the student protests in December 1986 and by espousing a “hurry-up” attitude towards economic reform.

From the point of view of the students, Hu was merely a symbolic victim of the regime, someone who looked like a half-decent reformer in the context of lesser-evilism. Simon Leys, a China critic of Orwellian insight and stature, explained the students’ attitude in this way:

“The hatred for the government is such that, in the eyes of the people, whoever is in disgrace must be a hero, and whoever is in power must be a scoundrel (which naturally entails the possibility for the same person to be in short succession a scoundrel, a hero, and then a scoundrel again, following the vicissitudes of his political career).” [1]

Hu’s death on 15 April and the subsequent memorial services provided an opportunity for the students to gather in relative safety to honour the reforms that he was accused of supporting. To the astonishment of both the students and the government, instead of what would have been a significant 10,000 students joining together, ten times that many showed up in Tiananmen Square, beginning several weeks of almost constant agitation.

The students’ early demands posed a threat to the government only in the audacity of their presentation; their content was hardly earth-shattering. The major points included calls for the reassessment of Hu’s “achievements”, for press freedom, for the public declaration of the assets and incomes of leading members of the government, and for the elimination of corruption. With these ignored, the students next insisted that the government meet with representatives of the demonstrators in a public dialogue.

Support for the students increased rapidly from then on, especially after a scathing editorial in the Beijing People’s Daily on 26 April denounced the student’s activities as a riot incited by a handful of “black-handed conspirators”. By 4 May cheering bystanders, applauding the students and filling Tiananmen Square, had grown in numbers until they outnumbered the students on the streets.

The most telling indication of public support was recounted to me in Beijing that day by a bank worker. He explained that the government, through its usual propaganda channel of political meetings held regularly in all work units, handed down its position on the students during the two weeks prior to 4 May. The authorities declared that the students, whom they acknowledged to be patriotic and loyal, must nonetheless return to their studies and desist in their disruptions of the government’s liberalization program, which would, of course, over a proper and gradual period meet their reasonable requests.

The paternalistic and disciplinarian character of the statement fooled no one and intimidated few people. The party officials presenting the position also directed workers to pass the message on to students—emphatically. The usual format of these meetings has the dictum presented first (only implicitly a fait accompli) followed by the democratic part: discussion. Typically in these circumstances, people use the discussion period as a means of gaining political merit by explaining why the government’s policy is a good thing. In this case, however, the discussions in many units in the Beijing area went so overwhelmingly against the government’s line that the word came down to cancel the discussion part of the meetings. Instead the Party tried such absurd tactics as passing out free cinema tickets to keep the workers off the streets on 4 May.

One of the more ironic corollaries of this saw many parents insisting that their children stay off the streets, fearing either their physical danger or loss of privilege, while they simultaneously supported the students’ criticisms and demands. This parental pressure and the fact that many students were on holidays over the 1 May to 4 May period (presumably at home) probably contributed greatly to the smaller numbers of students participating in the public events during this period.

The Early Days Outside of Beijing

Outside of Beijing protests were on a smaller scale probably because local authorities prevented most newspapers from reporting the events accurately if at all. Students in Shanghai found out what was going on only through the Voice of America radio broadcasts, which appear to have been somewhat inaccurate.

A worker in that city complained:

“In Beijing the students can protest and get away with it because they are the children of officials. People here are scared.” [2]

The small number of protesters in Shanghai were easily dispersed by the police.

The major demonstrations outside of Beijing occurred in Xian and Chang-sha during late April. In Xian, students sympathizing with the demands of those in Beijing held an evening public meeting. After the meeting, the students left the square but workers and other citizens moved in to fill the space, at which point the response of the police changed drastically. Apparently under orders not to harm students, they found the restriction very frustrating. One account indicated that the police were all too eager to beat people up; in the resulting fight, those who were originally bystanders responded with a rampage, attacking the newly built government headquarters and trashing and raiding stores. Significantly, they chose only privately owned stores and businesses—the ones selling luxury goods—and left the adjacent state-run firms alone. This discrimination results from anger over the high prices charged by the private businesses for goods that were scarce or non-existent in state-run stores and from growing feelings that the wealth of the new entrepreneurs comes from cheating and from privileged connections which give them access to these scarce products.

Martial Law

By mid-May a moderate line emerged ambiguously from the government, just in time to keep the students cool during the visit of the Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev. Yet Gorbachev’s visit proved to be highly embarrassing for the Chinese leadership, especially Deng Xiaoping, the ancient technocrat who held the crucial reins of power and for whom a rapprochement with the Soviet Union would be a crowning achievement on the eve of his retirement.

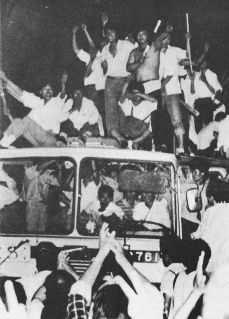

At the time of Gorbachev’s visit, three to four thousand students engaged in a hunger-strike at Tiananmen Square. This galvanized not only much larger numbers of students but also a sizable portion of the Beijing population into supporting the democracy movement. Groups of workers and intellectuals including government workers and journalists formed organizations and staged public protests. People gained more room to air their discontent than at any other time in the 40 years since the revolution.

For a few days it appeared that the so-called liberal faction within the Chinese politburo had created ground for a dialogue with the students. But things changed drastically after Gorbachev’s departure: on 20 May, Chinese premier Li Peng received the OK from Deng to declare martial law in Beijing. The key “liberal” figure, Communist Party general secretary Zhao Ziyang, disappeared from public view.

Between 20 May and 3 June unarmed troops tried several times to clear the demonstrators out of the centre of the city, each time being stopped by massive resistance, mostly on the part of non-student Beijing residents. In some instances the troops refused orders to move against the people. At the same time student leaders began to worry about the declining participation of Beijing students. Most of the local students, exhausted from over a month of continual activity and from the hunger strikes, retreated to their residences. They were being replaced, however, by a constant stream of students from distant cities. This later added to the complications of those who were trying to organize a safe withdrawal from the square in the face of a growing and ominous military presence; the out-of-town students had nowhere to go and no means of support other than that provided by the Tiananmen occupiers’ structure. [3]

In early June soldiers from distant regiments moved into the centre of the city with tanks and other armoured vehicles, although still without hand weapons. They clearly had little idea or appreciation of the motivations of the people of Beijing. Then, on 4 June the long-dreaded “final solution” of shoot-to-kill unleashed a blood bath in the streets of the city as the troops displaced the students in the square and crushed many of them and their artifacts of struggle, such as the sculpture of the goddess of democracy, printing presses, tents, and so on.

But the response by the citizens of Beijing was fierce: people continued to block the movement of soldiers despite their exposure to deadly gunfire, they seized and burned over 100 army vehicles, and they created roadblocks not only to stop the military but to bring normal life in the city to a halt.

Some Brief Impressions of the Current Transition

I had planned for well over a year to be in China during the spring of 1989, not knowing, of course; how opportune such timing would be. My initial travels through the south of the country quickly became a frustrating experience, as I found myself mired in the difficulty of arranging transportation as well as irritated by the hustling and less-than-honest dealings of the newly emerged mercantile class. Seeing all the worst aspects of human ‘greed and aggressiveness (although hardly any physical violence), I began to believe some of what Western reporters were saying about the emergence of Chinese capitalism.

The south of China “enjoys” the greatest amount of contact with the outside world. Much of the Western-style industrial development has taken place there, usually under the auspices and to the profit of Hong Kong and Japanese business interests. While people here seemed well-dressed and well-fed, I found the by-products of this imported style of prosperity scattered everywhere. Even when I walked along relatively remote ocean shores and the adjacent bush, I stumbled constantly upon plastic wrapping materials and discarded rubber sandals. Some students I talked to in Beijing readily admitted the seriousness of pollution in China, but their sighs, long faces, and silence in discussing it hinted that overcoming stalinism appeared to be an easier task than solving the waste problem in this country.

Urban areas in the south swarm with people trying to make fast bucks—from people pestering tourists to engage in some black-market money changing to bureaucrats arriving in brand-new, dark-tinted Japanese cars ostensibly to meet in air-conditioned hotel rooms for planning the future activities of their enterprises. My experiences led me to distinguish between people only in terms of whether or not they could make a buck off me: this determined whether they treated me like a sucker or a human being. Yet those who were nice were very nice, often helping me even though considerable difficulties might arise for them. Such a situation begs contemplation on the tensions arising in a society so polarized between generosity and greed, and this puzzled me until I reached Beijing.

I found Beijing cleaner, more relaxed, and characterized more by intellectual than commercial activity. By all reports, Beijing citizens were suddenly experiencing a thaw after years of living under the eyes of Big Brother. Political issues filled the air and many people eagerly sought Westerners to engage them in discussions of the current situation. But, of course, the answers received depended largely on what questions were asked, and journalists too often followed a line of thinking that implied Chinese students had nothing more in mind than the aspirations of Western consumers.

The Internal Power Struggle

Despite frequent promises to retire and hand power over to younger men, Deng Xiaoping—the prime mover behind China’s drive toward modernization continued to hang on and issue dictates, even, rumour had it, while physically immobilized in a hospital bed. Deng, like his equally stalinist adversary, Mao Zedong, frequently took advantage of spontaneous demands for democracy from the people in order to maneuvre his way into better positions for enacting his own agenda. The major protests of the last thirteen years all ended up giving more strength to Deng’s already heavy hand: the removal of the Gang of Four in 1976, the 1978 Democracy Wall movement, and student protests in 1984, 1985, and 1986.

While the West hailed him as a reformer once he began the “opening up” of China in the late seventies—rending it asunder might be a more appropriate description—Deng’s primary project has always been a barely concealed obsession with total state power. His economic reforms amount to nothing more than tools to this end, as do the various bureaucrats he hand-picked to manage the quickly developing economy. Deng’s many exhortations clearly express his philosophy: “to get rich is glorious”; “someone must get rich first”; “it doesn’t matter if the cat is black or white as long as it catches mice”; and, following from that latter bit of pragmatism: “practice is the sole criterion of truth”.

Under Deng a rivalry developed between a free-market faction of young, often Western-trained government advisors and an older-line group of bureaucrats jealously insisting on maintaining the heavily centralized state structure. Western investors, of course, sided with the former group with such an enthusiasm as to cause their defeat.

To begin with, the economy overheated to the point of high inflation and shortages of cash; this resulted in a political instability in the centre that turned against the reformers. Under siege, the latter group continued to claim that the political structure needed more loosening to allow the “free market” to operate smoothly. For example, under the old system all factories were required to send delegates to Beijing on a yearly basis to argue on behalf of the enterprise for all its basic needs: energy, raw materials, export quotas, foreign currency for equipment purchases, etc. (control over the labour force was held by the local Communist Party officials). While the central government minimized inflation by controlling prices, it made a mess of the rational allocation of resources; corruption played a more important role than scientific management in this case.

The loosening of this centralized control along with the introduction of many kinds of incentives created both a competition and an enthusiasm for production that China had not seen since colonial days. But those directly managing production gained the privileges at the expense of many of the bureaucrats in Beijing.

During the 80’s, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang became the chief managers of Deng’s schemes. But both of them favoured the free-market path too heavily for the majority of Communist Party bosses. Student demonstrations in 1986 were used as an excuse to demote Hu; Zhao started losing support by mid-1988 and by the time of the student demonstrations this year the members of his faction were suffering severe attacks from their conservative foes. The picture painted by the Western press of Zhao as friend of the people withstands very little scrutiny: his measures for implementing economic change would have included increased authoritarianism and martial law if necessary. In any case, his advisors, seeing the ship starting to sink, began to leave their posts in large numbers long before the students took to the streets this spring.

By late 1988 conservatives in the Chinese government had managed to enforce cuts in capital investment and to impose a two-year freeze on price reforms. Just the same, unemployment increased, inflation hit 30 percent in urban areas, and the government ran out of cash to pay peasants for their wheat shipments. While Zhao was certainly on his way out by April of this year, the size and force of the student movement probably inspired him to use it as a means of levering himself back into power. It didn’t work.

However, this describes only two poles competing inside the ruling hierarchy. The resistance to martial law within the Party and the turmoil within the army need not be interpreted just as rivalry between the pro-Zhao and the pro-Deng factions. The armies themselves apparently had their own rivalries and the cautionary letter written by the retired generals after martial law was declared probably arose from the common sense held by those not still jockeying for power.

Another letter protesting martial law that gained a mention in the Western press was written by the aging anarchist writer Ba Jin, still alive in Shanghai and prominent in the literary establishment after surviving many purges under Mao.

Corruption and the Rise of Capitalist Industry

A young woman student lamented to me that since the end of the Cultural Revolution many people had become too selfish, engaging in activities (such as small businesses) that provided gain only for themselves and not for the general social good. Part of her attitude is rooted in a traditional Chinese notion that buying and selling is a low-status activity.

Journalists have tended to view the conflict in China in terms of the classic struggle between capitalism and communism without caring to realize the extent to which the two have synthesized in many countries, East and West, creating a new form that is in many ways uglier than either of its predecessors: a highly centralized and authoritarian state carefully controlling—and benefiting from—a capitalist industrial and mercantile economy. The Chinese government encourages certain kinds of private enterprise, mostly small businesses owned by its own citizens or large and modern industrial plants where ownership is shared between the state and foreign capital. While more money stays in (very few) private hands than during the previous era, overall the assets controlled by the authorities increase.

The government policy of opening up the country to a kind of partnership of industrial enterprise has reinforced disparities in regional wealth because most of the foreign investment and foreign-style, industrialization has been located in the south. The most effective implementations of Western-style industrial capitalism have occurred in these so-called special economic zones. Sometimes individual wealthy Chinese own the corporations outright, but in most cases some level of government municipal, provincial, or national shares the ownership with foreign investors, who are usually based in Japan or Hong Kong. The United States has been the largest source of foreign capital and technology in recent years, but the direct involvement of US personnel in Chinese industry is less evident than that of Japanese and Hong Kong citizens. Although the US sold $740 million worth of military equipment to China in the last ten years, Japan is currently China’s largest trading partner. Even after the repression of the democracy movement, Japan showed very little restraint in its eagerness to continue its profitable relationship with its neighbour. Investors have flocked to China over the last ten years largely because of its cheap and disciplined labour force; disciplined, that is, in the sense that strikes are illegal. Westerners seem to have few complaints about this aspect of socialism. They would not, however, put up with certain other dimensions of state interference such as the highly regulated price and market structure established over the last 40 years. The reformers in the government managed to decrease the central bureaucracy’s control over the economy by loosening the long-standing restrictions over managerial decisions in a way that shifted accountability to the managers of each enterprise. And in no small way they boosted the spirits of entrepreneurs by removing price controls from much of the retail market. The resulting dual price structure allowed free enterprisers to buy many raw materials (state-controlled) cheap and sell at their own price since many of the new products had no competition in the market place. And exporters found their product costs in China to be considerably lower than elsewhere.

As a result, Chinese citizens able to round up the investment capital to start operations (mostly through connections to Western finance) became millionaires over night. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of these nouveau riche are children of high-ranking government and party officials. [4]

While the resulting transformation made China a hot place for investment, it also burned out much of the social welfare system that most Chinese had come to see as basic rights. The lack of constraint on prices and the unleashing of a tremendous increase in the buying power of even the small number of Chinese benefiting from free enterprise created a rate of inflation that severely hurt those on a fixed income, i.e., the majority of people. Yet the government found itself with a serious cash shortage as more and more of its capital became tied up in new equipment and the improvement of facilities for industry. Consequently, peasants are being paid by the government in promissory notes instead of in cash for this year’s harvest. Zhao proposed to deal with this overheated economy by speeding up the conversion of all goods into commodities whose prices would be affected by the market rather than controlled by the government. The stalinist bureaucrats were not impressed by the suggestion; the market chaos probably resulted in many temperate reformers returning to the ranks of these conservatives.

Labour Gets the Squeeze

The management of Chinese joint ventures usually consists either of personnel from the foreign partner or else of Chinese staff who will follow the procedures of efficiency, division of labour, and discipline as set out (and proven through experience) by the foreign group. The southern and coastal Special Economic Zones already have a large labour pool, but the government has been subtly encouraging other people to migrate to these areas. The workers provide labour under conditions significantly different from the usual Chinese factory: pay is geared to productivity, in some cases through piece-work schemes, and the foreign managers have virtually a free reign in organizing the activities of labour in ways which have seen success in the West. While the consequences raise the standard of living for some people in these regions, they also reproduce the typical social conditions of nations developing in the Western industrial style including discrepancies of wealth, competition and greed, and even unemployment. Those with high-skill jobs in the joint ventures don’t always reap the benefits of Western conditions. Engineers, for example, might on the books of the enterprise be receiving a salary equivalent to a foreigner in the same position but the government collects the difference between the 200 or so yuan (about US$54) that Chinese engineers earn a month and the three or four thousand dollars the company pays out.

Intending to make the labour pool more competitive, the government has allowed workers to migrate to the special economic zones in an unregulated way; one consequence is that official unemployment in Guangzhou is expected to surpass 100,000 this year. [5] The labour, of course, remains very cheap yet productivity becomes much higher here than in similar plants in other parts of China. No doubt the investment in up-to-date equipment gives an additional advantage to these operations.

Chinese officials in these special economic zones also gain perks. The government will allocate extra resources (privileges as well as cash) to facilitate smooth relationships between these Chinese intermediaries and foreign businesspersons. Many people, especially intellectuals and students, find it difficult to distinguish between these kinds of privilege and that old built-in fungus of hierarchy, corruption. A few years ago, for example, Hainan Island achieved special economic status and island authorities were allocated an exceptionally large amount of funds and permissions to improve its image and to provide the infrastructural means to properly engage foreigners in business transactions; in other words, they were allowed an unusually high number of icons of modernization like computers and cars. Consequently, in one year the island (one of the smallest provinces in the country) imported more cars than all the rest of the country combined. Very quickly, however, most of the cars found their way into the hands of the nouveau riche on the mainland, who had the money but not the bureaucratic means for importation.

Ironically, during the early stages of the student unrest in late April, the government announced the awarding of a 70-year lease to a Hong Kong-based Japanese company for the development of port facilities at Yang Pu harbour on Hainan Island. The foreign company will be taking control of 30 square kilometres of territory, building and operating the facilities (which include power plants, chemical plants, an oil refinery, and water supply utilities), and reaping the profits. Students in Shanghai, as well as some government officials and intellectuals, explicitly criticized this decision in their protests, pointing out the contradiction of not renewing Britain’s lease to Hong Kong in 1997 and then returning to the practice of granting “foreign concessions”—handing over Chinese resources to foreign imperialist powers. [6]

In fact the contradiction is not that great: China intends to keep the capitalist structure of Hong Kong intact, and the port facility on Hainan will clearly operate in a very similar fashion to Hong Kong industries. Hainan’s modern port will encourage Western purchases of Chinese goods and resources, and Beijing stands to earn a great deal of tax revenue, not to mention a pool of capital, when it takes over Hong Kong. Just the same, those who protest the deal with the Japanese clearly lack enthusiasm for capitalism as we know it.

Attitudes Towards Work

Except for the few people whose occupations bring them into a new and exciting contact with the West, virtually everyone I observed finds their job about as much fun as jail. Everywhere in stalls and stores, transportation, on the streets, etc., sour faces prevail on salaried workers. Only the petite bourgeoisie are interested in attaching a smile to their transactions; few people believe that such smiles are rooted in human kindness. I often amused myself by watching how people’s spirits would change in a split-second. A ticket-taker on a bus had the most animated of faces while engaged in a rapid-fire conversation with an acquaintance, but then her face seized up completely when it was time to yell out directions or collect money. Waitresses worked at a pace one might generously refer to as leisurely. They delivered food with an expression easily interpreted as hate-filled. And yet I felt somewhat astonished to receive bright, cheery smiles from these same waitresses if I thanked them when I left.

For forty years the Chinese revolution has guaranteed full employment—the so-called “iron rice bowl”—but the benefits of such a guarantee are largely negated by the attached strings. Once one obtains a job, one’s whole life is thereafter determined by the decisions of the work unit in charge of the labour force for that particular job. Central planners determine the nature and the quantity of the work to be done, wage levels, vacation time, housing, promotions, and so on. Once assigned to a work unit, a worker finds it virtually impossible to request transfer to another job; leaving a job is possible, but finding another one is normally very difficult.

Rarely do young workers have a choice in relocating to pursue their preferred career. To begin with, post-secondary students are channeled into their course of studies according to the prerogatives of the state. The more education a worker has, the more likely the state will assign that person to a particular job; personal desires are given little consideration. Not surprisingly, this situation lends itself to corruption; the children of important people often have connections that help the system work in their favour.

Once installed in a job, a person receives a set wage, regardless of the quality or quantity of work accomplished. This might sound like some variation of an egalitarian theme, but since the state assesses the wage less than generously, this condition satisfies few people. Any reminder that socialism’s victory over capitalism promises workers’ control over the structure or content of their work would no doubt cause harsh laughter. The obvious pointlessness of their work lives explains not only the indifferent attitude of the Chinese to their jobs but also the need on the part of the Chinese leadership to import Western managers and managerial techniques to instill other motivations for improving worker productivity.

Some motivations flaunt themselves on the street. I met a restaurant owner in Guangzhou who was riding one of the flashiest motorcycles I saw anywhere in China or South-East Asia. Happy to engage Westerners in conversation he invited myself and a friend to a meal (at a restaurant other than the one he owned) that cost nearly 200 yuan for four people. We had been accustomed to eating well on 4 or 5 yuan each. Given that 200 yuan a month is roughly an average wage for the Chinese, how could he afford it? Besides the income from his restaurant, he no doubt collected many “gifts” in his capacity as a contractor for the city; he stood directly in the doorway used by many Hong Kong and Taiwanese construction firms in their haste to reshape southern China’s skyline. As a consequence, he could claim an income of about 9300 yuan (US$2500) a month.

Students Confront the Political Environment

In the protests of previous years, students usually called upon a liberal within the regime to champion their demands. Sometimes some slight movements forward resulted, but always the government managed to side-step real change. By the Spring of 1989 students had learned the lesson painfully gained and so often lost by mass movements throughout history: don’t count on politicians. During their latest demonstrations, students referred to no living politicians in favourable ways; the time had come for them to press, unmediated, their own demands. The government tried to channel the protests through the established and conformist student organizations, a ruse for which the students in the street would not fall. They had been forming their own organizations secretly over a long period, and now these differently structured groups came out in the open, tentatively -at first, then with surprise at the strength of the encouragement they received.

While Western media sought to identify the leaders of the pro-democracy movement, it became clear that leadership was not an issue among the students. For one thing, leaders are the first targets of a repression; but visible evidence arose of the de-centralized nature of the political process within the movement. Voting on issues took place frequently among all participants. For example, immediately after the 4 May demonstrations students at each university voted independently on whether to continue the boycott of classes. The ballots, which included space for comments, were distributed one per dormitory room of six to eight people, who would debate the issue before reaching an agreement on the vote or else abstaining.

In all matters, discussion was continual and wide-spread. Many different organizations sprang up, some with parallel functions, yet none claiming to be the “sole voice of the people” and no faction fighting was evident. Spokespersons were never able to accurately predict how many people would show up for an action; indeed the entire life of the movement seemed characterized by spontaneity and flexibility, as if everyone had learned significant lessons of pragmatism from many previous demonstrations.

Capitalism, Communism, or Confusion?

Western observers tend to assume that the pro-democracy movement receives its main ideas from sources outside China, as if the West has a copyright on all ideas of freedom. Ironically, the Chinese authorities rant with the same argument and use it to rationalize their persecutions. Yet the majority of students have so little access to material on foreign politics and current affairs that such an analysis is at best weak and at least tinged with chauvinism. To complicate matters, Chinese students (not unlike students everywhere) learn about foreign political history in a context that must certainly work against an understanding of the development of democratic forms.

Such a variety of statements were collected from demonstrators, bystanders, and prominent students and intellectuals that almost any point of view can be supported. Yet most of the statements show a naivete or a lack of interest in political theory. Phil Cunningham, an American graduate student residing in Beijing, interviewed many students including Chai Ling, one of the three most visible (at least to Western journalists) of the Tiananmen hunger-strike organizers. Cunningham himself was given considerable U.S. television coverage in mid-June. After attempting reasonably accurate descriptions of the course of events, he was let loose to castigate the vicious “revolutionaries” in power in China, fully revealing his Rambo-like attitude towards communism. Considering this, one can see what he was fishing for when he precipitated this discussion with Chai Ling:

“Cunningham: Can democracy and communist socialism coexist?

“Chai Ling: I have not done any in-depth research into theory. I think democracy is a basic human need. I think it is not contradictory to the basic tenets of communism. The kind of democracy we are demanding is very natural, a kind of natural right. It is not hooked up with any ideology. We are only fighting for our own power….I wish that there will be a day when we can work safely in China. We shall harvest, labour, and enjoy the fruits of our work. We shall have the basic power to be human. We shall have personal security and participate in the management of the country. We shall have the power to determine the policies made by the leaders. We shall feel ourselves to be our own masters and that the country is our own. It will be the powerful nation for which we shall struggle, generation after generation.” [7]

Chai Ling’s response shows essentially a lack of interest in history and an inexperience in political struggle which explains some of the unpreparedness of the students. Yet she did not take Cunningham’s bait as an opportunity to endear herself in the hearts of millions of Westerners by condemning communism and endorsing capitalism. She does however express the real crux of the movement, a kind of nascent or gut-level anti-authoritarianism which believes that any system can be made tolerable when people control their own lives.

In this she effectively represents the vast majority of the democracy movement who see no contradiction in pursuing the road to prosperity through self-managed industrial development. In the above passage as well as in the following, one can see the effects of pervasive indoctrination of the Chinese Communist version of the Protestant work ethic. Unwittingly, I believe, she reveals a synthesis of capitalism and state socialism and lays bare the foundation of a class system even within a supposedly egalitarian point of view.

“Cunningham: Do you want to see a country with equality or one with disparity in wealth?

“Chai Ling: I don’t have the statistics. But I think the disparity between the privileged class in China and the ordinary people would be as wide as the disparity found in capitalist countries [possibly, she is speaking in the present tense here; substitute “might” for “would”). I would hope that after human nature is truly liberated in our society, a kind of natural harmonious regulation will come into effect. There will be differences. For example, those who are wise and hardworking will be able to reach a higher position in society. Those who are lazy and incapable will be at a lower position. This is a natural division and is not done deliberately. But now China is controlled by the exercising of [arbitrary?] power and this is abnormal. It is a manmade and unnatural condition. This movement has been accidental and was not premeditated. There is no governing theoretical framework. We just follow our feelings! It is spontaneous and a pure demand for democracy. We can see from the movement that the best and the most advanced elements are the students. They are right in front of the nation.” [8]

I believe that the final statement is more an expression of pride in the courage of students to stick their necks out than a definition of vanguardism. The spontaneity of the movement cannot be denied and as such provides at least a short-term protection against the emergence of an authoritarian leadership.

Further indications of the extent of anti-authoritarianism in the movement come from interviews with Wu’er Kaixi, one of the most dynamic of the student representatives in Tiananmen Square and number two on the Chinese government’s most-wanted list. That Wu’er’s critique of authority has considerable bite to it became clear to millions of Chinese as they watched him confront and insult Li Peng on live television, certainly a first for China. The next day martial law was declared.

While one cannot use Wu’er’s comments to describe with confidence the entire movement’s consciousness, they are similar to ideas that have arisen in many situations of mass agitation in other times and places. Most likely his comments and much of the sloganeering and many of the manifestoes produced by groups occupying Tiananmen Square result from the same process: intense discussions and debate heated up by the accelerating agitations of a mass movement.

Wu’er claimed that the students were demanding not just that the current government leadership step down but that the nature of its relationship to the people should change.

“There has to be a constraining political power, an improved democratic system, not just a change of ‘wise’ leaders…. [Li Peng] should treat himself as the child of the people, a civil servant of the people and the country….Reforms are useless, China needs revolution. Of course, I don’t agree with military revolution. What I mean is: they [the government] think the power should remain in the top of the government, but it should lie among the people.” [9]

Wu’er also makes references to “self-governed organizations”. Without giving too much weight to his words, I think it is fair to say that they represent a severe erosion of authoritarian discipline in China. Yet so little of this sentiment has been reported in the Western press.

Significantly, ABC news did not present any of the above excerpts from Cunningham’s interview even though they obviously had the entire discussion on videotape.

On the other hand, I know of only one incident where someone on the street volunteered capitalism as a goal of the democracy movement. This person reportedly expounded his desire to get rich as quickly as possible and referred to U.S. society as a model for China. No doubt millions of Chinese agree with this sentiment, but where were they while democracy was being debated in Tiananmen Square?

The absence of this entrepreneurial kind of voice cannot be explained by fear. To demand the overthrow of Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng is certainly more dangerous than to promote precisely that kind of activity in which the children of those two bureaucrats apparently excel. One can reasonably conclude that the majority of people involved in the democracy movement associated capitalism (admittedly, somewhat simplistically) with corruption and with the discrepancies of wealth that rapidly escalated as economic reforms proceeded, and perhaps distrusted it as a foreign ideology.

The Westerner on the receiving end of the above-mentioned fanfare for capitalism heard quite a different story’ from students to whom he was teaching English at Beijing Normal University. In mid-May he was asked in class how his fellow Canadians at home felt about the situation in China. He produced a clipping from the Toronto Globe and Mail quoting Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney on the inevitability of the Chinese people’s desire for capitalism. Unfortunately Mulroney was several thousand miles too far away to catch in the students’ laughter the ridicule he deserved. “Oh no, it’s much more complicated than that,” they explained. “We’re still socialists. It’s just that we want a socialism that we can control.” [10]

Indeed such attitudes indicate that the transformation of Chinese society into either the kind of capitalism dominant in the West or a new kind of highly disciplined state capitalism is encountering far more obstacles than either Western investors or the Chinese authorities had expected. In other words, the demonstrations that began in April make it clear that the Chinese are not running towards capitalism with wide-open arms and dazzling dreams of consumer goods.

The demands for increased freedom and for the suppression of corruption only make sense in the light of the disillusionment many people feel for the way in which a privileged few have enriched themselves to the detriment of the general good. This speaks more of a left-wing, critical attitude towards class society than of the more laissez-faire attitude towards class currently dominant in the West.

While the forms that the pro-democracy movement may take seem ambiguous, short-lived, and fragile, this autonomous resurgence of a struggle against the authoritarian state gives strong proof of the resiliency of the human spirit. The Chinese people demonstrate for all of us that even in a dark and totalitarian political world there is light at the end of the tunnel. Their actions also indicate that the promises and flaunting of material wealth by governments or corporations are no substitute either for freedom or for the confidence that tells people that they themselves are the ones best suited for determining the direction of their own lives.

Notes

1. Simon Leys, “When the ‘dummies’ talk back,” Far Eastern Economic Review, 144 no. 24, Hong Kong, 15 June 1989.

2. South China Morning Post, Hong Kong, 26 April 1989, p. 6.

3. My Information comes from an interview on 2 June 1989 with Wu’er Kaixi published in Pai Shing Semi-Monthly (Hong Kong?) 16 June 1989. My version is a mimeographed English translation done by a group of human rights activists and anarchists in Hong Kong. Further insights into the organizational problems of the so-called leadership come from a position paper by Tian Chun, apparently a member of one of the organizing committees of the Autonomous Students’ Union of Beijing Universities. His constructive critique of the organization to which he belonged deals mostly with formal problems and proposes a rather bureaucratic re-shaping of the groups running the day-to-day activities in Tiananmen Square. My copy of the position paper came from the same group of Hong Kong activists.

4. Peter Kwung and Dusanka Miscevic, “‘Bird-Cage Socialism’: China Gropes for a Way Out,” The Nation, 17 July 1989, pp. 73, 90-92.

5. Far Eastern Economic Review, 144 no. 22, Hong Kong, 4 June 1989 p. 70.

6. “Hainan port project clears its most difficult hurdle”, South China Morning Post, 24 April 1989, p. 1.

7. These passages are taken from a mimeographed transcription of an interview between Phil Cunningham and Chai Ling in Beijing on 3 June 1989. The conversation took place in Chinese and I have modified the English version I received from friends in Hong Kong in order to correct apparent translation/syntax errors.

8. Cunningham/Chai Ling interview; see previous note.

9. Wu’er Kaixi interview, Pai Shing Semi-Monthly (see previous note), as well as an interview broadcast by NBC, included in the same document.

10. Conversation with Perry Shearwood in Montreal, 31 July 1989.