I would like to invite your participation in an event that will remember Alexander Berkman on the centenary of his attempt to assassinate Henry Clay Frick during the Homestead Strike of 1892. This will not be an event glorifying the assassination of individuals as a political method, a technique Berkman himself came to question long after his attentat against Frick. Rather, the purpose will be to remember Alexander Berkman—the person, the author, the radical—on the 100th anniversary of the most important day of his life.

Most people have never heard of Alexander Berkman, and if they have, it is only in connection with his attentat on Frick or his relationship with Emma Goldman. He was, however, an authentic voice of radicalism, and his life is certainly worth remembering for a number of reasons, not the least of which being to rescue him “from the enormous condescension of history,” to borrow E.P. Thompson’s phrase. Berkman and his lifelong friend and companion, Emma Goldman, had a powerful impact on American society and American radicalism and, ultimately, became figures of international stature.

Berkman’s Attentat & Imprisonment

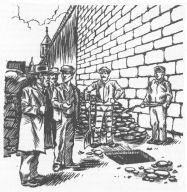

Steeped in the traditions of the Russian Populist movement, which out of necessity developed assassination as a political method, Berkman did not view his attempt on Frick as murder, but rather as a highly moral, self-sacrificing act of revolt—an attentat. He saw Frick, who had only weeks earlier sent armed thugs to Homestead to break the strike of honest workers, as the real murderer. Berkman himself was simply a vehicle of working-class vengeance, striking down the oppressor of the people. America, however, was not Russia, and Berkman’s attempt was to a large extent misunderstood. Public sympathy, which had been on the side of the strikers initially, turned against the strike as Frick recovered. Press and pulpit raged against the anarchist assassin, and Berkman’s attentat, ironically, worked against the Homestead workers he was trying to help.

Berkman paid dearly for his attack. Killing workers or taking away the livelihoods of families in the name of property or managerial prerogative was—and is—seldom punished; but killing in the name of anarchism was a sin of the highest order. In a trial that was merely a formality, Berkman was sentenced to 22 years detention, though legally he should have gotten a maximum of seven. He spent the next fourteen years in Western Penitentiary, buried alive. Even while suffering the medieval conditions of “Riverside,” however, Berkman accomplished much. He exhausted the prison library, teaching himself seven languages. He was instrumental in gathering evidence that led to a state investigation of the prison in 1897. In 1900, he masterminded a nearly successful escape attempt. Moreover, for years he was the object of an amnesty campaign of international scope, the headquarters of which was here in Pittsburgh. After he was released, he wrote the powerful, cathartic Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, a classic piece of prison and radical literature that, like Berkman himself, has almost been forgotten.

Living the Dream of Anarchism

In the years leading up to his and Emma Goldman’s deportation in 1919 (a case on which the young J. Edgar Hoover cut his paranoiac teeth), Berkman edited Goldman’s famous journal, Mother Earth, and his own paper, The Blast. He led protests against Rockefeller at the time of the Ludlow Massacre and was a tireless organizer for the IWW, the labor organization which most closely represented his views of anarchism. He also was a proponent and organizer of Ferrer’s Modern School movement. Falsely implicated in the Mooney frame-up in 1916, in the aftermath of the San Francisco Preparedness Day bombing, Berkman managed to escape Mooney’s fate of life imprisonment and devoted a good deal of time to Mooney’s, and fellow scapegoat Billings’s, defense. Using his connections with the anarchist movement in his native Russia, Berkman encouraged the legendary Petrograd “Free Mooney” demonstration that broadcast news of the frame-up around the world. Contemporaries and comrades of such notable individuals as John Reed, Jack London, Walter Lippman, Bill Haywood, Elizabeth Flynn, Eugene Debs, Kate Richards O’Hare, Margaret Sanger, Roger Baldwin, Max Eastman, and others of that “Reds” generation, Berkman and Goldman were foremost among the “movers and shakers” of that time, usually leading where others followed.

Goldman and Berkman were two of the few Americans to oppose U.S. involvement in World War I. Both were arrested and served time in prison for their anti-war and anti-draft agitation. At the same time, they also defied authority in spreading information about birth control, inspiring Margaret Sanger to start her eventually successful campaign. Berkman and Goldman both protested against and suffered the effects of America’s Red Scare, 1917-19. It was a difficult feat to dream the dream of anarchism in those days, and even more difficult to live it. Finally, at the end of 1919, both were deported to Russia aboard the infamous Buford, the leaky old ship filled with radicals being sent “back where they came from.” Frick died just before the deportation, prompting the quip by Berkman that Frick had at least left the country before he did, being “deported by God.”

Nowhere at Home

Sorry to leave America, Berkman was at the same time glad to return to Russia to be a part of the monumental changes that were happening there. At first, he threw himself into revolutionary activity.

Later, however, both he and Goldman became disillusioned with the Bolsheviks’ increasingly dictatorial rule, and, in fact, they became some of the very first critics of the excesses of the Communists. After failing to mediate between the Communist government and the rebellious Kronstadt sailors and witnessing the subsequent massacre of the Revolution’s Kronstadt stalwarts by Trotsky’s Red Army, Berkman and Goldman fell out completely with the ruling party and left the country. For the remainder of their lives, they were exiles, “nowhere at home.”

In the 1920s, Berkman produced several written works, The ABC’s of Anarchism and The Russian Tragedy among them. He also helped to organize the Anarchist Red Cross, one of the first international relief organizations for prisoners of conscience and a forerunner of organizations like Amnesty International. Berkman’s legacy of concern for prisoners continued into the 1950s through the work of the Alexander Berkman Aid Society. Eventually taking up residence in France, Berkman’s health began to fail. He committed suicide in 1936, just before the start of the Spanish anarchists’ fight with Fascism and, ironically, the successful unionization of the American steelworkers for whom he gave up a quarter of his life.

No doubt, there will be a lot of activities revolving around the centenary of the Homestead Strike in 1992. Few, if any, of them will recognize Berkman as anything other than a footnote or a fringe character. True, at the time, his attentat failed and even worked against the Homestead strikers, casting the Red shadow upon them. Still, Berkman’s attempt and his subsequent fourteen years in Western Penitentiary are an important, if often forgotten or deliberately ignored, part of history. I believe it is a part worth remembering.

Therefore, on or about July 23, 1992, the 100th anniversary of Berkman’s attentat, I would like to hold a combination symposium/concert in honor of his life and his place in our history. The event will, of course, be not-for-profit. Any admission charged will cover the expenses of publicity and speakers’ or musicians’ traveling expenses. Any monies over and above cost could be donated to Amnesty International, the Peltier Defense Fund, Freedom Now, or a similar organization dedicated to the protection and advancement of human rights and prisoners’ rights—something I think Berkman would go along with.

Contact: Gary L. Doebler, P.O. Box 22412, Pittsburgh, PA 15222 U.S.A. Messages: (412) 734-8339; Evenings: (412) 687-1088

Related

“Berkman’s Tunnel to Freedom” by Gary L. Doebler. FE #339, Spring, 1992

“‘Tony’ Revealed” by Gary L. Doebler. FE #377, March 2008

“Some Thoughts on Alexander Berkman’s Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist” by Marius Mason. FE #398, Summer, 2017