“History’s political and economic power structures have always abhorred ‘idle people’ as potential troublemakers. Yet nature never abhors seemingly idle trees, grass, snails, coral reefs, and clouds in the sky.”

— R. Buckminster Fuller

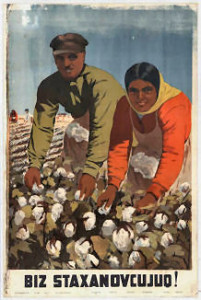

This year marks the one hundredth birthday of the Industrial Workers of the World union, but it is also the seventy-fifth anniversary of an event that symbolizes everything that the Wobblies battled against: that is, the perverse concept that work is ennobling, righteous, empowering and essentially has no bearing on class relations.

The most powerful (and depressing) example of this attitude was the rise of Stakhanovism. On August 31, 1935, a Soviet miner working in the Donets Basin in eastern Ukraine (still the site of one of the densest and most toxic concentrations of industrialized space in the world) reportedly quarried 102 tons of coal during his regular six-hour shift, a world record that represented almost fifteen times his regular, State-enforced quota.

The miner’s name was Aleksei Stakhanov, and the propaganda machine mobilized to celebrate his work on that day represents one of the worst, most despicable moments in the struggle to abolish wage slavery since the first Industrial Revolution.

Within days of Stakhanov’s ridiculous alleged achievement, the ruling Communist Party initiated a cult around productivist excess and began awarding State medals to individual workers and peasants who gloriously over-achieved. It took more than fifty years for the Soviet government to officially admit to having concocted Stakhanov’s superhuman tale for propaganda and economic purposes.

In late November 1935, the Party held an All-Union Stakhanovi e Conference featuring endless testimonials by zealous workaholics explaining how they managed to accomplish preposterously Herculean feats by their endless toil (usually through Taylorist, capitalist time-study methods), clean living, Stalinized socialism, and boundless patriotism for the USSR. Stakhanovites insisted that they could not have succeeded in the mines, in the fields, or on the shop floor if it wasn’t for their somber reverence for neatness, good hygiene, and strict on-the job obedience.

Many of the most fanatical Stakhanovites extolled the genius of Stalin for creating a progressive piece-rate pay scale that rewarded above-quota production and pitted individual workers against one another in ferocious competition for the meager incentives. One of Stalin’s remarks during his keynote address at the Stakhanovite conference became the official slogan for the hyper-worker: thanks to manic industrialization and escalated drudgery, “life has become better and happier, too.”

Soon thereafter, the Stakhanovite became a prominent part of the pantheon of State heroes. Motion pictures, newsreels, plays and novels portrayed the lives and endless successes of Stakhanovites, as well as the selfish schemes of the unscrupulous, hung-over, counter-revolutionary slackers (in Russian, a bezdelnik) who tried to ruin workplace morale. Stakhanovite magazines featured advertisements for hard-to-find luxury items (big apartments, automobiles, perfume) which were only available to those outstanding go-getters who labored harder, longer and better than anyone else at work. (In the USA, Time magazine featured Stakhanov’s portrait on its front cover in mid-December 1935 above the headline “Workers of the World Unite for his Wife’s Lingerie and Perfume.”)

With the lure of commodities, these organs of the Soviet state encouraged people to strive to become “two-hundreders” (those who produced twice their quota in a single shift) or, better yet, “one-thousanders” (1,000% more than their work quota). They also provided information on house-cleaning and the best recipes that a dutiful wife could prepare for her frenetically industrious husband who needed to maximize his energy. Meanwhile, special industrial training seminars were created to drill foremen and managers in how to Stakhanovize their labor force.

The motivations of the Stalinist bosses for creating this workerist myth is obvious when you consider the historical context. The rise of the Stakhanovite celebrity masochist occurred in 1935, right smack dab in the middle of Stalin’s second Five-Year Plan (1933 through 1937). During those years, the Soviet government was desperate to jump-start and advance state-capitalism under the guise of Marxism.

The Soviet economy was massively geared toward heavy industry, dams and electrification projects, and the production of munitions, and there were few consumer goods available to the average family. Government food distribution was unreliable and often provided inedible rations. As in the Western capitalist societies that had been devastated by the Great Depression, wages were lower than they had been in the previous decade, and a severe affordable housing shortage created abysmal living conditions for most Soviet families.

Consider, too, the fact that, not long after launching the Stakhanovite propaganda project, Stalin set about erecting a new and very harsh regime of labor discipline, starting with the criminalization of worker absenteeism and penalties of two to four months prison time for quitting your job.

In January 1939, the government passed a new law defining absenteeism to include being more than 20 minutes late to work or leaving 20 minutes early—the consequences for breaking this 20-minute rule included mandatory dismissal and loss of social benefits (food, housing, medical treatment). Failure to enforce these new laws meant that bosses and law enforcement officials could end up in jail themselves.

Bringing the State’s repressive police apparatus to bear on workplace issues provides a good indication of how desperately the Soviet government depended upon labor stolen from workers under the banner of “life has become better and happier.” Profit, after all, can only exist when excess (unpaid) labor is hoarded and traded while the heavy iron wheels of production keep turning for as little expense as possible.

In short, the make-believe stories of nationwide Stakhanovite success was meant to pacify Soviet laborers with the same flavor of hogwash being consumed in the West: shop floor competition and intense individual toil was all that was needed to get ahead in a capitalist system, be it market or state-capitalism.

As in the US, this tactic diverted people’s attention away from the realization that their collective misery is systemic and instead encourages them to believe that their wretched lives are the result of personal moral failure.

As a cautionary tale, the seventieth anniversary of the founding of Stakhanovism is as important to the history of the anti-work movement as is the centenary of the start of the IWW. The Wobblies have always been about refusing work and not participating in the creation of the profit needed for capitalist development—one of the union’s slogans on the picket line was “I Won’t Work.”

The Wobs opposed the unremittingly coercive technologies of time-management, surveillance, discipline and control as demoralizing, inhuman and alienating. There will always be petty arguments about whether or not the IWW was influenced more by Marxism, anarchism or anarcho-syndicalism. But it would be a mistake to categorize Wobbly calls for “self-management,” “worker autonomy,” “point-of-production organizing” and “direct democracy in the workplace” as a form of workerism.

As Fred Thompson explored in the introduction to a 1989 reprint of Paul Lafargue’s The Right to Be Lazy, the Wobblies are, above all else, “forerunners of a future in which work and leisure are indistinguishable purposeful activities, far from inane, self-directed, freed from all taint of commodity culture because we work for the fun of it and get what we want for free.”

Even when they were fighting for safer working conditions, shorter work days, and higher pay, the IWWs were the polar opposite of the Stakhanovites. In fact, the Stakhanovite would probably be regarded by the Wobbly as a “scissorbill”—in his 1933 pamphlet The General Strike IWW poet and soapbox speaker Ralph Chaplin described the scissorbill worker as someone whose mind “belongs to the last editor, speaker or politician who filled the aching void with insidious poison or anti-proletarian misinformation. Such workers not only play the sucker end in the shell game of capitalism, but they also are too dumb and blind to figure out what has happened when things go wrong.”

In short, he or she is “a wage-slave with a capitalist mind; a decaying middle-class mind,” one whose unquestioned faith in and respect for the capitalist wage system, private property, God, fatherland, and the food-chain of authority prevents him or her from comprehending that the work ethic—as well as work itself—has to be eradicated, not cherished.