As a publication appearing only three times a year, it’s difficult to report on the outrages of capital and the empire in a timely fashion. Usually, we cover only issues not available elsewhere. However, the Greek events of this Spring seem worthy of reporting and analysis as Capital’s crisis becomes generalized and rulers’ call for austerity enforced on workers becomes more shrill.

What follows is an edited version of the Ta Paida Tis Galarias (The Children of The Gallery) group report on the Spring demonstrations in Athens against austerity measures, including the events leading to the tragic deaths of three bank workers and its implications for the movement of opposition.

Although in a period of acute fiscal terrorism escalating day after day with constant threats of an imminent state bankruptcy and “sacrifices to be made,” the proletariat’s response on the eve of the voting of the new austerity measures in the Greek parliament was impressive. It was probably the biggest workers’ demonstration since the fall of the dictatorship in 1974, even bigger than the 2001 demo which led to the withdrawal of a planned pension reform.

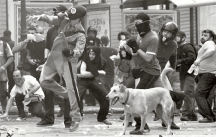

We estimate that there were more than two hundred thousand demonstrators in the centre of Athens May 5 and about fifty thousand in the rest of the country. There were strikes in almost all sectors of the (re)production process. A proletarian crowd similar to the one which had taken to the streets in December 2008 (also called derogatorily, “hooded youth” by mainstream media propaganda) was also there equipped with axes, sledges, hammers, molotov cocktails, stones, gas masks, goggles and sticks.

Although there were instances that hooded rioters were booed when they attempted or actually made violent attacks on buildings, in general they fit well within this motley, colourful, angered river of demonstrators. The slogans ranged from those that rejected the political system as a whole, like “Let’s burn the Parliament brothel” to patriotic ones, like “IMF go away”, and to populist ones like “Thieves!” and “People demand crooks to be sent to prison”. Aggressive slogans referring to politicians in general are becoming more and more dominant.

The demo by the PAME (the CP’s “Workers’ Front”) was also big (well over20,000) and reached Parliament’s Syntagma Square first. According to the leader of the CP there were fascist provocateurs carrying PAME placards inciting CP members to storm the Parliament and thus discredit the party’s loyalty to the constitution!

Although this accusation bears some validity because fascists were actually seen there, the CP leaders had some difficulty with their members in leading them quickly away from the square and preventing them from shouting angry slogans against the Parliament. It’s maybe too bold to regard it as a sign of a gradual disobedience to this monolithic party’s iron rule, but in such fluid times no one really knows. Soon, crowds of workers (electricians, postal workers, municipal workers etc.) tried to enter the building from any access available but there was none as hundreds of riot cops were strung out all along the forecourt and the entrances. Another crowd of workers of both sexes and all ages confronted the cops who were in front of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, cursing and threatening them.

Despite the fact that the riot police made a massive counter-attack with tear gas and fire grenades and managed to disperse the crowd, there were constantly new blocks of demonstrators arriving in front of the Parliament while the first blocks which had been pushed back were reorganizing in Panepistimiou St. and Syngrou Ave. They started smashing whatever they could and attacked the riot police squads who were strung out in the nearby streets.

Although most of the big buildings in the centre of the town were closed with rolling shutters, they managed to attack some banks and state buildings. There was extensive destruction of property especially in Syngrou Ave. Luxury cars, a tax office building and the Prefecture of Athens were set on fire and even hours later the area looked like a war-zone.

The fights lasted for almost three hours. It is impossible to record everything that happened in the streets. Just one incident: some teachers and other workers managed to encircle a few riot cops belonging to Group D, a new squadron of riot police on motorcycles and thrash them, while the cops were screaming “Please no, we are workers, too”!

Soon, the terrible news from foreign media outlets came on mobile phones: three people dead in a burned down bank!

There were some attempts to burn down banks in various places but in most cases the crowd didn’t go forward because there were scabs locked inside them. It was only the building of Marfin Bank in Stadiou St. that was finally set on fire.

Just a few minutes before the tragedy started, however, it was not “hooded hooligans” who shouted “scabs” at the bank employees but organized blocks of strikers who swore at them and called them to abandon the building. Given the bulk of the demo and its density, the turmoil and the noise by the chants, it’s obvious that a certain degree of confusion–common in such situations–makes it difficult to provide the accurate facts concerning this tragic incident.

What seems to be closer to the truth (from fragments of information by eye-witnesses put together) is that at this particular bank, right in the heart of Athens on a general strike day, about 20 clerks were made to work by their boss, got locked in “for their protection” and three of them died of suffocation.

Initially a molotov cocktail was thrown through a hole made in the window panes into the ground floor. However, when some bank clerks were seen on the balconies again, some demonstrators called them to leave and then they tried to put the fire out.

What actually happened then, and how, in no time at all, the building was ablaze, remains unknown. The macabre series of events that followed with demonstrators trying to help those trapped inside, the fire brigade taking too long to take some of them out, the smiling billionaire banker being chased away by the angry crowd have been well reported.

Later, the prime minister announced the news in the Parliament condemning the “political irresponsibility” of those who resist the measures taken and “lead people to death” while the government’s “salvation measures” on the contrary “promote life”.

The reversal was successful. Soon, a huge operation by the riot police followed. The crowds were dispersed and chased away, the whole centre was cordoned until late at night, Exarchia was under siege, an anarchist squat was invaded with many arrests, the Immigrants’ Haunt was invaded by the cops and trashed and persistent smoke over the city as well as a sense of bitterness and numbness would not go away.

The consequences were visible the next day: the media vultures capitalized on the tragic death presenting it as a “personal tragedy” dissociated from its general context (mere human bodies cut off from its social context) and some went so far as to criminalize resistance and protest.

The government gained time by changing the subject of discussion to the bank deaths and the unions felt released from any obligation to call for a strike the very day when the new austerity measures were passed. Nonetheless, in such a general climate of fear, a few thousand gathered outside the Parliament at an evening rally called by some unions and left organizations.

Anger was still there, fists were raised, bottles of water and some fire crackers were thrown at the riot cops and slogans both against the parliament and the cops were chanted. An old woman was begging people to chant to “make them [the politicians] leave”, a guy pissed in a bottle and threw it to the cops, few anti-authoritarians were to be seen and when it got dark and the unions and most organizations left, people, quite ordinary, everyday people with bare hands would not go. Attacked with ferocity by the riot police, chased away, trampled down Syntagma square steps, panicked, but angered young and older people got dispersed in nearby streets.

A crackdown on anarchists and anti-authoritarians has already started and it will get more acute. Criminalizing a whole social-political milieu stretching out to far left organizations has always been used as a diversion by the state and it will be used even more so now.

However, framing anarchists will not make those hundreds of thousands who demonstrated and even the many more who stayed passive but worried, ignore the IMF and the “salvation package” offered to them by the government. Harassing our milieu will not pay people’s bills nor guarantee their future, which remains bleak.

It is more than clear that the sickening game of turning the dominant fear/guilt for the debt into a fear/guilt for the resistance and the (violent) uprising against the terrorism of debt has already started. If class struggle escalates, the conditions may look more and more like the ones in a proper civil war.

The question of violence has already become central. In the same way we assess the state’s management of violence, we are obliged to assess proletarian violence, as well. The movement has to deal with the legitimation of rebellious violence and its content in practical terms.

As for the anarchist-antiauthoritarian milieu and its dominant insurrectional tendency, the tradition of a fetishized, macho glorification of violence has existed for too long and consistent for us to remain indifferent now. Violence as an end in itself in all its variations (including armed struggle) has been propagated constantly for years. Especially after the December rebellion, a certain degree of nihilistic decomposition has become evident, extending over the milieu itself.

On the periphery of this milieu, a growing number of very young people are promoting nihilistic, limitless violence and “destruction” even if this includes attacks on scabs, “petit-bourgeois elements,” and “law-abiding citizens.”

Condemnations of these attitudes and a self-critique to some extent, have already started in the milieu. In hindsight, such tragic incidents, with all their consequences might have happened, in the December rebellion itself.

What prevented them was the creation of a (limited) proletarian public sphere and of communities of struggle which developed not only through violence, but through their own content, discourse, and other means of communication. It was these pre-existing communities of students, football hooligans, immigrants, anarchists that turned into communities of struggle by the subjects of the rebellion themselves that gave violence a meaningful place.

Will there be such communities again now that not only a proletarian minority is involved? Will there be a practical way of self-organization in the workplaces, in the neighborhoods or in the streets to determine the form and the content of the struggle and thus place violence in a liberating perspective?

Uneasy questions in pressing times, but we will have to find the answers struggling.