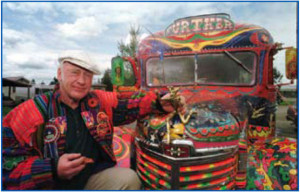

Fifty years ago, July 1964, a 1939 school bus furnished with bunk beds, basic kitchen facilities, and wired-up audio equipment, sets out from Palo Alto, California to journey across America. It is painted in bright psychedelic colors with the destination sign of, “Further,” on the front and, “Caution: Weird Load,” on the rear. It carries on board ten or so 60s drop-outs from various walks of life, as the bus makes its erratic way towards Route 60 and the road to New York.

At the wheel is Neal Cassady, friend of Jack Kerouac and star of the 1950s cult novel, On the Road. Inspiring and leading the mixed gang of academics, artists, musician, and writers, is Ken Kesey, author of the 1962 cult novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, who, near the start of the journey, states the group’s mission statement:

What I hope will continue to happen, because it’s already starting to happen. All of us are beginning to do our thing, and we’re going to keep doing it, right out front, and none of us are going to deny what other people are doing.

Kesey wants to be in New York City for the publication of his second novel, Sometimes a Great Notion, and has the idea about using the trip to say something to and about 60s America. If Beat author, Jack Kerouac made one journey across America from East to West in the previous decade, Kesey would make another in the reverse direction. Homage would be paid.

The two authors would meet up although there would be no meeting of minds, but this trip would be on a larger and louder scale. With music blaring, lights flashing, and LSD (still a legal substance) in plentiful supply, this bunch of raucously stoned and oddly dressed travellers, these self-styled Merry Pranksters, want to offer straight suburban and corporate America a glimpse of an alternative re-configured reality–subversive and surreal in equal measure.

There are no speeches or banners, but there is an invitation to experience something new and strange, even if it’s only watching Neal Cassady drive the Further bus backwards at speed down Phoenix’s main street.

Although the 1964 journey is Kesey’s best-known prank, he had started his project to startle and disturb America earlier and would continue it after the wheels of the bus had stopped turning.

There is his decision to participate in 1960, as a 25 year old creative writing student, in a CIA-funded research program at Menlo Park Hospital to investigate the effects of mind-control drugs. He ensured, with a comic irony that he surely appreciated, that his first experience with LSD and similar substances was provided by the US government itself.

If communist North Korea can employ brain-washing techniques to undermine American democracy, the US also wants its own Manchurian Candidate. And fresh-faced Ken Kesey, trying to bridge the unlikely gulf between his budding career as a wrestler and his wished-for career as an author, is signed up at $75 a day to report back on the impact of his drug consumption.

Not known for his willingness to follow orders, it isn’t long before Kesey is stamping his own imprint on the hospital’s experiments. Asked by one doctor, interested in testing the way LSD affects the mind’s sense of time, to indicate when a minute has passed, Kesey simply measures his pulse.

And required by medical science to have hallucinations, it isn’t perhaps surprising that he wants others to share the experience, to bridge the short distance between the hospital and the semi-bohemian suburb of Perry Lane where he lives, by carrying LSD and mescaline and other psychedelic mixtures from the one to the other. Not everybody is keen to take up Kesey’s invitation, but there are enough curious residents to ensure that his first prank, turning on a group of university students and academics with the government’s own chemicals, is a success.

From then on, pranksterism is at the center of Kesey’s youthful life. Tested-out fictionally in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest through McMurphy’s various attempts to upstage Nurse Ratchett and challenge her authority, pranking becomes a way of creating events that disrupt conventional routines and forms of hierarchical control in a highly conformist society.

One kind of event is the Acid Trip. Beginning in 1965, after the disillusioning experience of the Cow Palace Beatles’ concert, where the Pranksters watch teenage girls turn into robotic zombies, the Pranksters put together events in which a combination of drugs (especially LSD), sound, strobe lights, and dancing create a totally immersive and liberating world; a world that, in the words of Jerry Garcia (leader of The Grateful Dead) is “meant to do away with old forms, old ideas.”

As word about the Acid Tests spreads across the San Francisco area, they become larger and larger in size, with increasingly sophisticated and imposing technology. However, tensions arise between the purist Pranksters and more commercial influences. Also, there are growing concerns that Kesey, proponent of democratic freedom, is taking too dominant a role, and although a number of people suffer a series of bad trips, for a time in the mid-sixties, the Tests offer spaces in which new forms of individual and collective identity and experience can emerge.

Inside the Test, you are able to forget your old self, life, and relationships, forget your old dependence on reason and habit and achieve a type of transformation, even transcendence. However, as LSD is made illegal in California in 1966, it isn’t the desire for transcendence that inspires the idea to smear the walls of San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom with DMSO, laced with LSD, the intended site of the Acid Test Graduation of Halloween.

Rather, it is the prospect of turning-on the 6000 members of the Californian Democratic Party due to attend a huge rally there the following night. While the decision of the leading promoter to pull out causes a change of plan, just the thought of it is enough to suggest the extent and nature of Kesey’s ambitions. He may not be a politician but his pranks certainly have a political dimension.

Stoning the Democratic Party is one way of forcing an encounter between different worlds. Another is to make friends with the Hells Angels. Invited over to Kesey’s Californian home in La Honda in early August 1965, their black leather gear, massive bikes and deserved reputation for violence sharply contrast with the colorful, laid-back and arty Pranksters.

Anything might kick off a bad scene–a wrong word here, a miscalculated action there–but nothing does. The motorcycle outlaws seem tamed, even sitting quietly while gay, Jewish poet, Allen Ginsberg, does his Tibetan chants. Used to fear and shock, here the Angels are just accepted and made part of the scene.

The bikers drink their beer and take the LSD they are offered, willing, at least temporarily, to go with the flow. For a few weeks, Kesey has constructed a weird, comic and risky cultural experiment in which a new community, composed of unlikely elements is formed; another prank to test and reshape social reality.

There may be little similarity between the Hells Angels and the Unitarian Church, but the latter also provides the Chief Prankster with an opportunity to stir together another unusual mix. After an invitation to attend the church’s 1965 annual California conference, Kesey arrives with his fellow pranksters in the by-now famous bus.

While, from the start, there is certainly tension, even hostility, between the two groups, there are also moments of collusion, even harmony as when Kesey’s burning of the American flag is followed by the congregation singing America the Beautiful. Or, when the Pranksters and Unitarians wash each others’ feet in the Pacific to show humility or when some of the latter share a night on the bus listening to and making music.

The older generation of Unitarians might want Kesey out, but he has made his contribution, created happenings that have cut across differences. The strange clothes, the weird behavior, the loud music, the drugs, all de-stabilize settled assumptions and practices, turning an institution on its head, at least for a week. The prank has worked.

Rather lower-key and more personal is Kesey’s attempt in 1966 to evade capture by the police for drug-possession by faking his own death. Creative and fun to prepare and theatrically disorientating in its effect–the poetic suicide note, the drive to a cliff near Eureka, California by a Kesey look-alike, the smashed-up car and the boots left forlornly on the beach–it’s not difficult to appreciate why the prank would appeal. The police, however, catch on to the trick but for a while at least reality is suspended.

After Kesey’s return from Mexico, to where he has absconded, he is arguing that the Pranksters need to go beyond LSD to find new ways of challenging the status quo. The nature of these new ways remain rather vague, but the effect is to further intensify the movement’s decline. By 1968 Kesey is back farming and writing in Oregon and the Trips, and similar events, are in the hands of others.

Although Kesey’s sector of the psychedelic moment doesn’t last that long, there is a legacy. The Yippies of the late 1960s recognize the potential of real-life theatre to wake people up to the actuality of their world, creating, for example, semi-comic chaos in New York’s Macy’s Department store when they take on the role of shop-assistants.

And, more recently, the anti-globalization movement and a range of protest groups in the UK, Turkey and Russia have made use of different forms of performance art to gain publicity for their cause.

Think Pussy Riot. Kesey’s brand of Pranksterism may have died but its spirit is still alive and well.

Mike Peters is a UK-based adult education tutor with an interest in writing about links between politics and culture.

Ken Kesey lived from 1935 to 2001.