As we go to print, it is with great sadness that we report the passing of our compañero, amigo, padre, and abuelo, Federico Arcos, in Windsor, Ontario, at the age of 94. The last several months were very difficult for him, but all in all he lived long, fully, and admirably. He stood for lasting and noble human values. He cared about human beings and the Earth. He believed in justice and freedom and human solidarity and compassion. He had a powerful and permanent effect on us.

For now, since we can’t write at length about our dear friend, we are publishing the following text, based on a tribute addressed to him in Detroit on his 80th birthday.

Federico was the son of gente humilde, obreros. He grew up breathing the air of anarchist fervor in the old CNT districts of Barcelona in the 1920s and ’30s. One of his early memories was of reading the anarchist press aloud to the gathered compañeros and vecinos in his neighborhood because not all could read.

When the revolution came in 1936, he took his place in the fight, doing what needed to be done, whether it was teaching a comrade to read, running through a firefight to fetch ammunition, or sharing a crust of bread–giving his energy and youth fully to el Ideal, and learning in the process that such sacrifice brings greater rewards than anything the egoism of bourgeois society could ever offer.

Federico suffered for his beliefs and principles. He saw the revolution defeated. He was forced into exile in France where he had to hide from the Vichy police. After returning to Spain, he spent time in jail and was forced into compulsory military service. He later participated in the anti-Franco underground, and saw many of the friends of his youth die in the underground movement and in exile.

In 1952 he emigrated to Canada and found a vibrant anarchist community across the river in Detroit, mostly Europeans—Spaniards, Eastern Europeans, and Italians. Federico was one of the youngest members of that community. In the 1970s he found us, and in time became our elder, our abuelo.

Federico worked much of his life in a Ford factory. He was a loyal and respected rank-and-file union comrade, participating in the historic 110-day Canadian Auto Workers strike in Windsor in 1955.

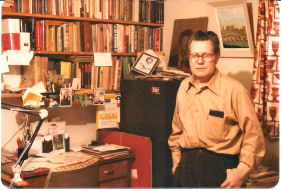

Meanwhile, he gradually gathered one of the foremost anarchist archives in North America, indeed, in the world, in his modest home. He is thanked in numerous books by historians who came to work there and were welcomed and usually fed by Federico and his wife Pura Arcos, who had her own anarchist history, and whom we dearly loved. (Pura died in 1995. We will reprint her memorial in our next issue.)

Federico loved poetry, produced a charming collection of his own, with elegies to his fallen comrades and meditations on the human condition. He was a compendium of poems, songs, and proverbs, and could recite impressive amounts of poetry by heart. He believed in the power of the word, just as he believed in the power of love, of friendship, of loyalty, of justice, of freedom.

Federico lived modestly, deriving his pleasures not from material things or from empty status but from solidarity and a revolutionary passion. He was a dedicated comrade, always arriving early to work on projects or to visit friends. He never suggested putting something off that could be accomplished immediately. He stepped forward, even as his knees, or back, or lungs sometimes protested against his spirit.

From his youth as a member of los Quijotes del Ideal in the Barrio de Gracia in revolutionary Barcelona in 1937, to his involvement in Black & Red and the Fifth Estate, he maintained his ideals and principles. He proved by example that one may lose great historic battles, and yet triumph in life.

One of Federico’s most vivid stories was from after the fall of the Spanish Republic in 1939, when the refugees, Federico among them, were crossing into France, ill, dispirited, unsure of the future, and weak with hunger. He would recall with a smile and a kind of wonder how they gathered acorns to eat there under the oaks, and how they were sustained.

Those who have read Don Quixote will likely know that since classical times the oak tree has been a symbol of the Golden Age. Behind young Fede Arcos (as his friends knew him), not yet nineteen years old, lay the ruins of one of history’s brief Golden Ages, and one of the most sublime dreams human beings have dreamed.

Ahead lay great uncertainty—and we know now, more violence, calamity, disappointment. But the compañeros y compañeras gathered and ate the acorns and were sustained. And their dream sustains us.

Federico Arcos lived a life of passion and commitment with that new world always in his heart, reminding us, as Rousseau once remarked, that the Golden Age is neither before us nor behind, but within.

Related: See “Remembering Federico Arcos” by David Watson, Fifth Estate #395, Winter 2016.