Recycling is a classic case of co-optation.

The title of this article is somewhat misleading since I continue to recycle a portion of the waste produced daily by my household. What has changed is my previous diligence in making certain every scrap of what is recyclable winds up in my yellow curbside container.

Now I use my recycle bin solely because my trash has to be placed somewhere for disposal. However, if I had to make any concerted effort at all, such as sorting or transporting my trash to some facility, I’m sure I wouldn’t bother.

I realize even the headline is a provocation to some people who see recycling as an important component in the campaign for a clean environment. However, the contention that this is an inadequate perspective, leading eventually to the opposite of its intent, is nothing new to the Fifth Estate. *

Recycling is a classic case of cooptation by the reigning powers of genuine sentiment for reform. The idea of reprocessing waste items was put forth as a good faith solution by those in the ecology movement who saw the damage being done to the environment by the detritus of production and consumption.

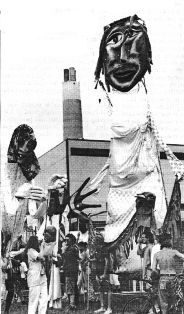

The 1980s gave rise to the construction of a rash of huge incinerators, including one in Detroit. This monstrous facility, the world’s largest at the time of construction, sits three miles from the downtown area, less than a mile from the homes of several FE staff members.

This insane techno-fix (doesn’t everyone know burning anything produces toxins?) has as its basis the idea that we can continue current waste levels without having to pay the consequences.

Any sort of conservation or recycling is officially discouraged since these babies need all the fuel they can get, often to meet contract requirements with local utilities to produce electricity. Unfortunately for the environment and the people living in the immediate area (almost always poor and/or minority), these incinerators emit a deadly stream of dioxins, furans, and heavy metals into the air which assault our immune system.

Even with all the evidence about toxicity levels emanating from incinerators, their fires remain stoked, and they continue to produce toxic ash (as much as 30 percent of what is burned needs to be buried in special landfills to contain their now-concentrated poisonous content).

Economically, incinerators are flatlining all over the country due to their inability to produce the electricity for which they contracted to utilities. At one Detroit area burner, the operating authority has set up a special marketing division to seek trash from surrounding municipalities, and Canada if necessary, to meet its fuel needs.

In contrast, recycling seems like a reasonable alternative, particularly since it doesn’t confront either our personal consumption level or society’s aggregate mess. The daily demand is that people place recyclables in a separate bin, something with which most good citizens were willing to comply even when not required by local ordinance. In municipalities where curbside recycling isn’t provided as a city service, many people willingly make trips to recycling centers with their sorted trash feeling “they’re at least doing something.”

However, the “something” is illusory. Landfills remain the major destination for the majority of household garbage and when space runs out like it has in New York’s Fishkill facility, the city contracts to have it shipped to sites in Virginia.

A quick visual check in your neighborhood should illustrate that recycling isn’t significantly reducing the trash that will either be landfilled or incinerated. Estimate the volume in the non-recycled section of your trash or on your block compared to the relatively tiny amount in recycling containers. My box is filled maybe every two weeks, much of it with newspapers, but every week I set out one or two 30 gallon garbage cans. And that’s with at least some consciousness on my part about waste, excessive consumption and the composting of All my vegetable matter.

Mad Levels of Production

Some people argue that if recycling is not effective it at least functions as a gesture and is an important element towards understanding individual responsibility for our mess. However, the notion that recycling is even a little better than nothing produces only more illusions, not environmental sanity. Mad levels of production and consumption are at the core of capitalist economies, and unless that process is confronted, little will change.

To some extent this essay about individual disposal of household garbage should only be a footnote when talking about waste. Americans generate 8.5 billion tons of waste yearly, but the vast majority-98 percent-is from industrial and mining operations. The remaining two percent—172 million-is from municipal sources. According to the Summer 1990 Earth Island Journal, the latter totals out to an average of 1,360 pounds per person yearly for households, but a whopping 31 tons (!) for each of us from the major sources.

The emphasis on household recycling functions as a diversion from examining the big sources of waste. A close look at the myths about recycling shows they are being perpetrated less by those committed to ecology and more by those doing the most damage to the planet. Even those active in administering recycling programs have come to recognize, for instance, that plastics consumption (an increasing percentage of the waste stream) is actually encouraged by recycling. For that reason, the Berkeley Ecology Center (BEC) announced in February 1996 that it would no longer accept plastics in the recycling program they administer for that California city.

Though they don’t use it in production, the American Plastics Council, an industry group for virgin resin manufacturers (first-time-use plastics) has been a relentless promoter of plastics recycling. They’ve recently spent $18 million on public relations as part of a propaganda campaign to change the long-standing perception of their product as harmful to the environment.

From its inception, plastic has been a synonym for the false and insubstantial. The late Frank Zappa sang about “plastic people” and the obscenely whispered advice to “The Graduate,” similarly was, “Plastics.” Unfortunately, the businessman in the 1967 film ultimately was correct; the future did lie in that multi-use substance made from the oil for which the U.S. was willing to kill several hundred thousand Iraqis. The substitution of plastics for glass, wood and paper products has been so substantial that hardly anyone even notices. Any public event, a baseball game for instance, produces massive amounts of plastic cups, plates and cutlery that have been used in some cases for only the seconds it takes to spill down ten ounces of beer before being consigned to a trash barrel.

Toxic For Every Moment

The cups arrive at the local landfill (they can’t be recycled), there to remain intact for hundreds of years, although their slow disintegration begins to release toxins. They began their ignominious journey in an oil field thousands of miles away and were toxic every moment of their existence-from drilling to oceanic transportation, to off-loading at American harbors to manufacture and finally to disposal. Plants that pump out benzene and vinyl chlorines, building blocks for a wide spectrum of plastics, produce 14 percent of U.S. toxic air emissions. Sixteen percent of all industrial accidents-explosions, toxic cloud releases, chemical spills and fires-involve plastic production. Recycling doesn’t touch this, but the spills and accidents aren’t what are featured in industry ads.

Recycled plastic is a small percentage of what is manufactured and the amount is actually decreasing even as recycling increases. In 1993, for instance, 15 billion pounds of plastic were produced from what the industry calls virgin feed stock, but only one billion pounds of that was recycled.

And, the “at least we’re doing something” argument doesn’t work well here either. The industrial process which reclaims plastic is highly toxic and much of what is collected is shipped overseas, and processed under uncontrolled conditions in notorious polluting countries like China and Thailand. In addition, most of the products which are manufactured from what is recycled, such as park benches, traffic strips, and polyester jackets, can’t be recycled a second time. So, what you set out at your curb is only one generation away from a landfill.

Michael Garfield, director of the Ann Arbor (Mich.) Ecology Center, notes that although all plastic containers bear the chasing arrows symbol with a number in the middle, suggesting that all such products are recyclable, it is only 1s and 2s that can be. He says, “Recycling these are only slightly better than letting them go into a landfill, given the amount of resources expended.”

He’s being generous if you compute the amount of energy needed to ship your leftover designer water bottle to China along with millions of others to be reprocessed, manufactured into a new item, then shipped back to the U.S., transported to a mall, purchased, used, discarded, and finally landfilled.

It’s interesting to note how the last imperative in the ecological triad of reduce, reuse, recycle, has emerged as the one given prominence. The consequences of demanding an emphasis on the first-reduction of production-puts one on the path of confrontation with the Megamachine, something few people are willing to undertake. For instance, a campaign against plastic demands opposition not only to oil as a world commodity, but also to what the empire is willing to do to defend it.

As I write, the U.S. plans for another military strike against Iraq to insure its control of Middle East oil are on hold, but the generals and politicians are still in a blood froth. A good ecologist now needs to do more than just put tin cans in a curbside recycling bin. It requires being an antiwar activist as well.

*See my “Recycling & Liberal Reform,” in our 1990 Earth Day Special, an 8-page supplement, or in the Summer 1990 FE. Send $2 for the latter; postage for the former.