I arrived early at Clutch Cargo’s, once an imposing church, but now a trendy rock joint in yuppified downtown Pontiac, a gritty, predominantly black, industrial Detroit suburb. The occasion was a concert by Chumbawamba, the anarchist pop group from Leeds, England, which has achieved international acclaim for their catchy hit, “Tubthumping.”

I arrived early at Clutch Cargo’s, once an imposing church, but now a trendy rock joint in yuppified downtown Pontiac, a gritty, predominantly black, industrial Detroit suburb. The occasion was a concert by Chumbawamba, the anarchist pop group from Leeds, England, which has achieved international acclaim for their catchy hit, “Tubthumping.”

The song is so ubiquitous—”I get knocked down, but I get up again; you’re never going to keep me down”—that not only has it topped the charts in Europe, North America and Asia with triple platinum sales, but is now played at sporting events worldwide, supplanting staples such as Queen’s, “We Are The Champions.” The song, featured on a promotional compilation for the new VW Beetle, was heard recently on cheesy TV shows like “Beverly Hills 90210,” and “Veronica’s Closet” and is also on the sound track of the Hollywood production of “Home Alone 3.”

To most listeners, there’s little more to Chumbawamba than a band with a pop hit featuring an infectious hook that everyone will probably be sick of by the time this is read. But Chumbawamba is an unlikely candidate for commercial stardom. Probably unknown to most of the group’s newly acquired fans, the group has long been a favorite of the international anarchist community for their uncompromising songs challenging the political state and capitalism. The band’s origins go back 15 years in the British punk movement, and its members define themselves as revolutionary anarchists.

Their recent limited edition, “Showtime,” distributed by AK Press, an anarchist publisher, is a double-CD with a Noam Chomsky speech featured on the second disk. On it, the band plays a live performance before an enthusiastic crowd in a Leeds pub during a two-day benefit for the local Anti-Fascist Action organization. During the concerts, a defense guard was on hand to protect the venue from English neo-nazis who had threatened to attack the event. During the night following the first performance, the pub’s windows were smashed, but the second evening came off without incident.

Revolutionary Anthems

Chumbawamba played Detroit in 1993 at 404, a small storefront anarchist club that held about 50 people comfortably. That August night, with temperatures in the 80’s outside, about 75 sweaty people jammed into the space, many of them stripped to the waist, and danced wildly to the band’s infectious music and cheered their explicit revolutionary anthems.

Alice Nutter, one of the band’s vocalists, remembers the event. “Yeah, we had to put Boff’s amp on the cooker [the stove],” she says, “and we had to stop every once in a while to ask if anyone wanted to go to the toilet.” The place was so crowded that the musicians were blocking the entrance to the only bathroom.

Four years later, the band is at the pinnacle of international fame and many people in the anarchist milieu are wondering whether success will spoil Chumbawamba. How does a group that has been featured in every publication from The New York Times to USA Today deal with fame and still hang on to its anti-authoritarian principles?

When the doors to Clutch Cargo’s opened, the first rush of patrons looked as though they had just been dropped off by their moms from a Saturday afternoon at a shopping mall. In ran a stream of hyper-enthusiastic 11-, 12and 13-year-olds, followed by their parents, many who decidedly looked like they had been dragged to a concert they didn’t want to attend. Eventually the audience was mainly comprised of adults, but a friend told me later, as if to emphasize Chumbawamba’s popularity with pre-teens, “Yeah, They’re my eight-year-old’s favorite group.”

A Rousing Hand

I was there with several striking Detroit newspaper workers at the invitation of Nutter whom I had interviewed for Detroit’s weekly Metro Times. Several days after I spoke with her, I wondered whether she was aware of the almost three-year strike against the two local dailies, fearing one of the scab papers might try to get an interview with members of the band. My call was too late. Alice had already talked to a scab reporter and was anguished; she hadn’t known of the boycott. She offered to let the strikers speak from the stage before their performance and set up a literature table in the lobby along with one from the local chapter of Anti-Racist Action (ARA).

Given all the kids in the audience, we didn’t know what the reaction would be to a labor message, but when Barbara Ingalls, a locked-out printer, took the stage she got a rousing hand. Later, during the performance, Danbert Nobacon, another of the vocalists, dedicated a song to the strikers and took a newspaper boycott sign on stage with him.

So far, so good. But Chumbawamba’s latest album, “Tubthumper,” was a mystery of sorts to many of their long-time U.S. admirers. It was released in the U.S. on Universal, a major corporate label, and gone were the explicit anarchist lyrics denouncing oppression. Although tubthumping is the old name for radical street corner speaking, the latest lyrics are a gentler, more ambiguous set with nothing in them to directly suggest their core politics. Their big hit, a corny tribute to indominatability also celebrates the male culture of drinking at sporting events—”He drinks a whisky drink; he drinks a vodka drink; he drinks a lager drink.”

The answer to our curiosity as to whether we were going to see a domesticated Chumbawamba came with the first song-one of their old ones—”Give the Anarchist a Cigarette”—”Nothing burns down by itself,every fire needs a little help.” And, as if to assure the audience this was a band whose commitment remains intact, the next tune was another oldie, “Mouthful of Shit,” which the band dedicated to British Prime Minister Tony Blair and U.S. President Bill Clinton.

Although many of the tunes they played were from their latest album, others were clearly anarchist and anti-religious. It was impossible to determine what the soccer moms and their kids thought while sitting through this, but when the band finally sang “Tubthumping,” the whole place exploded. Everyone was on their feet singing the chorus in unison, throwing their fists in the air, and then it was over. An encore? Sure. They did an a cappella version of their earlier “Homophobia” just so the words, which are sometimes lost in their English Midlands accents, were perfectly clear—”Homophobia, the worst disease; love how you want and love who you please.”

Following the performance, Nutter told us how two days earlier the band had taped a performance of “Tubthumping” for TV’s David Letterman Show. In the middle of the song they began chanting, “Free Mumia Abu-Jamal,” before going back to the famous chorus. The show’s producers went apoplectic saying they believed Mumia was innocent, but that he was a “convicted cop killer” and the band would have to do the segment again or it wouldn’t air. After a short conference, the group members refused and left the studio.

Much to their surprise, the segment ran as recorded, but Nutter commented afterward, “I don’t think we’ll be invited back.”

After the band appeared January 20 on ABC-TV’s “Politically Incorrect” with Bill Maher and repeated the shoplifting advice her band often gives in interviews, twelve Virgin Records megastores in Los Angeles took “Tubthumper” off their shelves and put it behind the counter. Nutter said she believed it was just “fine” for poor people to shoplift records from chains.

“We were dismayed by her saying this kind of thing,” whined Christos Garkinos, Virgin marketing vice-president. “Especially since we were one of the band’s early supporters.”

Nutter said it was Maher who singled out Virgin as a possible target, and she attempted to change the topic to “why people can’t afford records and feel the need to shoplift in an unequal world.”

Nutter defends the less confrontational character of the band’s new lyrical direction and insists that their intent remains unchanged. “We don’t want to just get our pop music into people’s homes,” she says. “We want to get anarchist ideas along with it.”

Although there is little on their current album to overtly suggest this perspective, band members say this wasn’t a marketing strategy. They had completed the album a year before signing with EMI in Britain after being dumped by their independent label which advised the band to “Take a year off and write stronger songs.”

Pointing to an earlier recording, Nutter says, “If you look at our album, ‘Pictures of Starving Children,’ the way those songs are written, they’re just theses. Each song has at least 32 lines, none of them repeated, and no chorus, because we were trying to get in as many words as possible.” She says they wanted to do music with “choruses and hook lines, and were constructed like ordinary pop songs.” Nutter says the band decided if they wanted to “really touch people,” they had to “put the ‘theses’ somewhere else.”

Unfortunately, with the U.S. release of “Tubthumper” on Universal, only half of their equation worked. They’ve got their top-of-the-charts music on MTV, on kareoke machines and at sporting events, but most people, like the prepubescent kids at Clutch Cargo’s, were clueless as to the “theses” that ultimately animate Chumbawamba. An ad for a record chain in a local Detroit paper informed potential buyers that “this was the group’s eighth album. Previously known for their politically charged lyrics, they toned down the social commentary just a bit on this album.”

Anarchist Spin

The “somewhere else” for the theses mentioned above was supposed to be the latest album’s liner notes. The band spent months finding quotes from historic and contemporary radical figures that would give an anarchist spin to words which in themselves don’t directly convey that message. These were contained in a thick booklet accompanying the CD in its European and Asian release. However, Universal’s American lawyers threw up a roadblock-demanding a clearance on each quote. This would have delayed the debut of the album for months and left the band in an untenable position—a further wait for its release or an expurgated version. They chose the latter.

“Maybe we could understand about a quote from Orwell,” Nutter says angrily, “but do you have to get clearance on ownership of anonymous graffiti taken from a wall in Paris in 1968?” She expresses frustration about how the album appears without the liner notes: “People in Europe and Asia got the album we wanted; in America they didn’t. The last thing in the world we are is lap liberals; we’re anarchists.”

Following the lyrics of each song in the truncated booklet that appears with the American release is an invitation for people to write or e-mail the band for the missing quotes.

Of course, the debate about what constitutes “selling-out” is a complicated one, and hardly new to rock and roll. Obvious examples, from the early ’70s include Detroit’s seminal rock band, the MC5 and folksinger/anti-war activist Phil Ochs, whose efforts to reach wider audiences with a reduced social message failed miserably. Although groups such as the Clash and Gang of Four achieved mainstream success through innocuous hit songs, they soon self-destructed over the dilemma of how to keep radical politics intact.

The band’s milder lyrics, instant fame, and decision to sign with a major label aren’t without critics in the radical movement from where Chumbawamba sprang. Class War, a militant British anarchist organization and newspaper denounced the band on their web site (www.angelfire.com) for Chumbawamba’s decision to sign with EMI, a multinational media conglomerate and military contractor.

Commenting on bands signing with major labels prior to her group’s contract with EMI, Class War quotes Nutter as saying in an interview, “I’ve too often heard rebel bands excuse their participation with big business by saying ‘we’ll get across to more people.’ I’d be interested to discover exactly what they’ll get across and to whom. Turning rebellion into cash so dilutes the content of what they’re saying that I no longer think that they’re saying anything.”

There are obvious contradictions between a band that aspires to revolution and a corporation which seeks advantage in the international capitalist market place. AK Press pressed 7000 copies of Chumba’s “Showtime” CD, but “Tubthumper” will probably top out at quadruple platinum and only a corporation can do the worldwide distribution necessary for this sort of demand.

Musically there’s not much to distinguish “Tubthumper” from their recent albums, but lyrics needing supporting quotes or explanations to achieve the radical thrust the group desires suggest an inherent weakness. Although the band sees the new album’s songs as threaded together, the themes by themselves don’t seem to portray more than a protest against the anonymity and falseness of modern society. “One by One,” does indict bureaucratic labor leaders and “Scapegoat” criticizes blaming others, but as the band laments, they could easily come off as “lap liberals” when the music stands by itself.

Nutter’s criticism of their previous music seems curious. Many of their older tunes such as “Never Do What You Are Told,” “That’s How Grateful We Are,” and “Homophobia,” had the hooks and choruses she mentions approvingly. Their “I Never Gave Up” is an earlier “Tubthumping,” with a similar theme—”I crawled in the mud, but I never gave up”—not stated quite as elegantly, but certainly with a memorable chorus.

To their credit, the band seems intent on using their fame to promote anarchist ideas. After a U.S. tour in late 1997, they headed back to England to do a series of benefits for several rape crisis centers and anti-fascist groups. “We were influenced by bands like Crass with the idea pop music could be intensely political,” Nutter recalls. “They introduced us to the idea that songs didn’t have to be about love, and they called themselves anarchist. Chumbawamba doesn’t want to be just a pop group. We also want to be part of a radical community away from music because real life is more exciting than a rock and roll circus.”

As to the question of success affecting them, she says, “As soon as it starts to spoil us, we have to give up what we’re doing.” Asked about the band’s future plans, “To be in ‘Home Alone 4,'” Nutter jokes.

Note: The suppressed liner notes are available from Chumbawamba, PO Box TR666, Leeds LS12 3XJ, UK or at www.chumba.com. “Showtime” can be ordered from Fifth Estate Books.

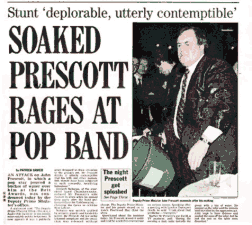

Sidebar: Chuba Soaks Brit Deputy PM

Sidebar: Chuba Soaks Brit Deputy PM

Chumbawamba made international news Feb. 9 when two of their members poured a bucket of ice water over the head of the British Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott, at a posh music awards dinner. The action received extensive press and TV coverage. The following is a report we received from Chumbawamba.

We’d already spent part of the evening trying to get passes for people outside who were protesting against the treatment of workers by Polygram, a record company employing people at practically slave labour rates in the UK. Security with bow-ties and red faces were scanning the seated arena for any sign of trouble. Walkie-talkies were spitting and crackling. [Chumbawamba’s] Danbert and Alice decided to have a quiet word with Mr. Prescott and his party, bent on steering the conversation around to New Labour’s despicable treatment of 500 sacked Liverpool dockworkers.

The bucket of iced water at Prescott’s feet was too tempting. Taking his cue from the infamous custard-pie attacker in Belgium who recently covered the visiting Bill Gates in yellow goo, Danbert carefully aimed the whole thing at our Great Leader’s Understudy and saying, “This is for the Liverpool dockers,” poured the whole lot over his New Labour suit.

Danbert was immediately seized by security and led away by cops. Mass panic everywhere. Head plain-clothes cop seeing his Head Of Security promotion going down the drain. People laughing. Cops not knowing what to do. “What’s your name? Who are you with?” Prescott decided not to press charges in order to avoid the debacle of a court case where the second-highest political figure in the country tries to sue someone for wetting his suit.

The next morning we wrote a press release to explain why the Deputy prime Minister had been “attacked.” It stated in part:

“This wanton act of agit-prop is dedicated to single mothers, sacked dockworkers, people being forced into workfare, people who will be denied legal aid, students who will be denied the free education that the whole Labour front bench benefited from, the homeless, and all of the underclass who are now suffering at the hands of the Labour government.”