a review of

Army of None: Strategies to Counter Military Recruitment, End War, Build a Better World by Aimee Allison and David Solnit, 2007, Seven Stories Press, 194 pp.

“War is good business, invest your son!”

— Vietnam-era slogan

The authors’ task of denying cannon fodder to US imperial forces for its endless wars may be easier than it appears. Sure, the military spends a fortune each year (almost $5 billion) to convince young people to join up. The Pentagon recruitment advertising budget, for all its ubiquitous pitches-television, radio, movie theater, and Channel One in-school commercials, rock videos, on-line video games with six million registered users, a magazine aimed at pre-teens, recruiter visits to colleges and high schools, displays at job fairs, all coordinated by a Defense Department half- billion dollar joint Advertising Marketing Research Studies project charged with creating a database of 30 million 16 to 25 year olds-really doesn’t do very well. Recruits are important because there’s really no better way of sabotaging the war effort than to cut down on the amount of personnel available to wage it. Not only does it weaken the ability of a State to conduct a successful military occupation, it also hampers its capacity to expand its aggression to new corners of the globe. The US armed forces have a difficult time meeting recruitment quotas, having missed their quarterly goals last year. Most poor, working class, and lower middle-class youth have no interest in joining the military no matter what promises are given or the economic circumstances in which they find themselves (in a recent Pentagon-financed study, a whopping 61% of youth under 25 reported that they will “definitely not serve”). Perhaps 1% of the population ever joins the military.

I don’t buy the leftist apology for those willing recruits of the imperial armed forces that says essentially it’s a poverty draft: desperate, poor youth join to escape ghetto, barrio, or rural poverty. To be sure, that–added to the dishonest sales pitches of recruiters (Army of None informs us that 65% of recruits who sign up for the Montgomery GI Bill receive no money for college and only 15% ever earn a college degree)–impels a lot of young people to see enlisting as a ticket out of an impoverished community. But don’t any of them watch TV and see the US military at work in Iraq destroying cities, terrorizing families after breaking down their doors, and hear the reports of massacres committed by “our” troops?

Of course they do. Plus, anyone who has watched even a World War II movie knows that army life is about strict discipline, getting yelled at by a psycho drill sergeant, and being sent into the mouths of cannons. It’s a personality type and not poverty that gets someone to agree to become part of this.

In devising strategies to overcome this combination of naivete, romanticized notions of warrior values, and a desire to be part of a war machine, the authors of Army of None provide a manual for depriving the military of that small percentage of youth they need to continue their wars. Co-author Allison is a vet who received a conscientious objector discharge from the Army Reserves, and Solnit is a long time activist and organizer, best known for his role in the 1999 Seattle demonstrations against the WTO and the creator of the giant puppets seen at so many actions.

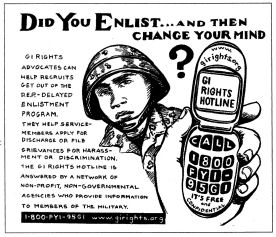

Army of None defines the extent and techniques of recruitment efforts (most of them shocking), but then gives practical tips on how to build and maintain an active counter-recruitment organizing effort in your community. Stories of success from Pittsburgh to Santa Cruz are heartening, and the efforts to include vets and people of all ages shows the power of cross- generational anti-war organizing. Included are suggestions on how to deal with the media and how to organize opposition to recruitment efforts. The book has a large text format, bullet points and lots of graphics making it easy to read on the fly between meetings and demos.

Solnit’s organizing efforts have taken him around the world, so the book concludes with an emphasis on creating People Power outside of the official channels. A tools and resources section is extremely valuable, particularly for people without previous organizing experience.

I’ll end as I began with another Vietnam era slogan, “FTA!,” or “Fuck The Army!” That one was from the soldiers themselves.